SMAC: The StarCraft Multi-Agent Challenge

Multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) is an exciting and growing field. A particularly interesting and widely applicable class of problems is partially observable, cooperative, multi-agent learning, in which a team of agents must learn to coordinate their behaviour while conditioning only on their private observations. These problems bring unique challenges, such as the nonstationarity of learning, multi-agent credit assignment, and the difficulty of representing the value of joint actions.

However, a lack of standardised benchmark tasks has limited progress by making it hard to test new ideas and compare algorithms. In contrast, widely-adopted environments such as the Arcade Learning Environment and MuJoCo have played a major role in the recent advances of single-agent deep RL.

To fill in the gap, we are introducing the StarCraft Multi-Agent Challenge (SMAC), a benchmark that provides elements of partial observability, challenging dynamics, and high-dimensional observation spaces. SMAC is built using the StarCraft II game engine, creating a testbed for research in cooperative MARL where each game unit is an independent RL agent.

The full games of StarCraft: BroodWar and StarCraft II have been used as RL environments for some time, due to the many interesting challenges inherent to the games. DeepMind’s AlphaStar has recently shown a very impressive level of play on one StarCraft II matchup using a centralised controller. In contrast, SMAC is not intended as an environment to train agents for use in full StarCraft II gameplay. Instead, by introducing strict decentralisation and local partial observability, we use the StarCraft II game engine to build a new set of rich multi-agent problems.

StarCraft

In a regular full game of StarCraft, one or more humans compete against each other or against a built-in game AI. Each player needs to gather resources, construct buildings, and build armies of units to defeat their opponent by conquering its territories and destroying its bases.

Similar to most RTSs, StarCraft has two main gameplay components:

- Macromanagement (macro) refers to high-level strategic considerations, such as the economy and resource management.

- Micromanagement (micro) refers to fine-grained control of individual units.

Generally, the player with the better macro will have a larger and stronger army, as well as a stronger defensive scheme. Micro is also a vital aspect of StarCraft gameplay with a high skill ceiling, and is practiced in isolation by professional players.

StarCraft has already been used as a research platform for AI, and more recently, RL. Typically, the game is framed as a competitive task: an agent takes the role of a human player, making macro decisions and performing micro as a puppeteer that issues orders to individual units from a centralised controller.

StarCraft II, the second version of the game, was recently introduced to the research community through the release of Blizzard’s StarCraft II API, an interface that provides full external control of the game, and DeepMind’s PySC2, an open source toolset that exposes the former as an environment for RL. PySC2 was used to train AlphaStar, the first AI to defeat a professional human player in the full game of StarCraft II.

SMAC

We introduce the StarCraft Multi-Agent Challenge (SMAC) as a benchmark for research in cooperative MARL.

In order to build a rich multi-agent testbed, SMAC focuses solely on unit micromanagement. We leverage the natural multi-agent structure of micro by proposing a modified version of the problem designed specifically for decentralised control. In particular, we require that each unit be controlled by an independent RL agent that conditions only on local observations restricted to a limited field of view centred on that unit. Groups of these agents must be trained to solve challenging combat scenarios, battling an opposing army under the centralised control of the game’s built-in scripted AI.

Here’s a video of our best agents for several SMAC scenarios:

Proper micro of units during battles maximises the damage dealt to enemy units while minimising damage received and requires a range of skills. For example, one important technique is focus fire, i.e., ordering units to jointly attack and kill enemy units one after another. Other common micromanagement techniques include: assembling units into formations based on their armour types, making enemy units give chase while maintaining enough distance so that little or no damage is incurred (kiting), coordinating the positioning of units to attack from different directions or taking advantage of the terrain to defeat the enemy. Learning these rich cooperative behaviours under partial observability is a challenging task, which can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of MARL algorithms.

SMAC makes use of PySC2 and the raw interface of StarCraft II API to communicate with the game. However, SMAC is conceptually different from the RL environment of PySC2. The goal of PySC2 is to learn to play the full game of StarCraft II. This is a competitive task where a centralised RL agent receives RGB pixels as input and performs both macro and micro with the player-level control similar to human players. SMAC, on the other hand, represents a set of cooperative multi-agent micro challenges where each learning agent controls a single military unit.

Differences between PySC2 and SMAC

| PySC2 | SMAC | |

|---|---|---|

| Setting | competitive | collaborative |

| Control | player-level | unit-level |

| Gameplay | macro & micro | micro |

| Goal | master the full game of StarCraft II | benchmark cooperative MARL methods |

| Observations | RGB pixels | feature vectors |

| Replays available | yes | no |

SMAC is composed of 22 combat scenarios that are chosen to learn different aspects of unit micromanagement. The number of agents in these scenarios ranges between 2 and 27. For the full list of SMAC scenarios, please refer to the SMAC documentation.

State and Observations

The local observations of agents include the following information about both allied and enemy units which are within the sight range:

- distance

- relative x

- relative y

- health

- shield

- unit type

- last action (only for allied units)

Agents can also observe the terrain features surrounding them; particularly, the walkability and terrain height.

Additional state information about all units on the map is also available during the training, which allows training the decentralised policies in a centralised fashion. This includes the unit features present in the observations, as well as the following attributes:

- coordinates of all agents relative to the map centre

- cooldown / energy

- the last actions of all agents Note that the global state should only be used during the training and must not be used during the decentralised execution.

Actions

Agents can take the following discrete actions:

- move[direction] (four directions: north, south, east, or west)

- attack[enemy id]

- heal[agent id] (only for Medivacs)

- stop

An agent is permitted to perform an attack/heal action only towards enemies/allies that are within the shooting range.

In the game of StarCraft II, whenever an idle unit is under attack, it automatically starts a reply attack towards the attacking enemy units without being explicitly ordered. We limited such influences of the game on our agents by disabling the automatic reply towards the enemy attacks and enemy units that are located closely.

The maximum number of actions an agent can take ranges between 7 and 70, depending on the scenario.

Rewards

Agents only receive a shared team reward and need to deduce their own contribution to the team’s success. SMAC provides a default reward scheme which can be configured using a set of flags. Specifically, rewards can be sparse, +1/-1 for winning/losing an episode, or dense, intermediate rewards after the following events:

- dealing health/shield damage

- receiving health/shield damage

- killing an enemy unit

- having an allied unit killed

- winning the episode

- losing the episode

- Nonetheless, we strongly discourage disingenuous engineering of the reward function (e.g. tuning different reward functions for different scenarios).

Results

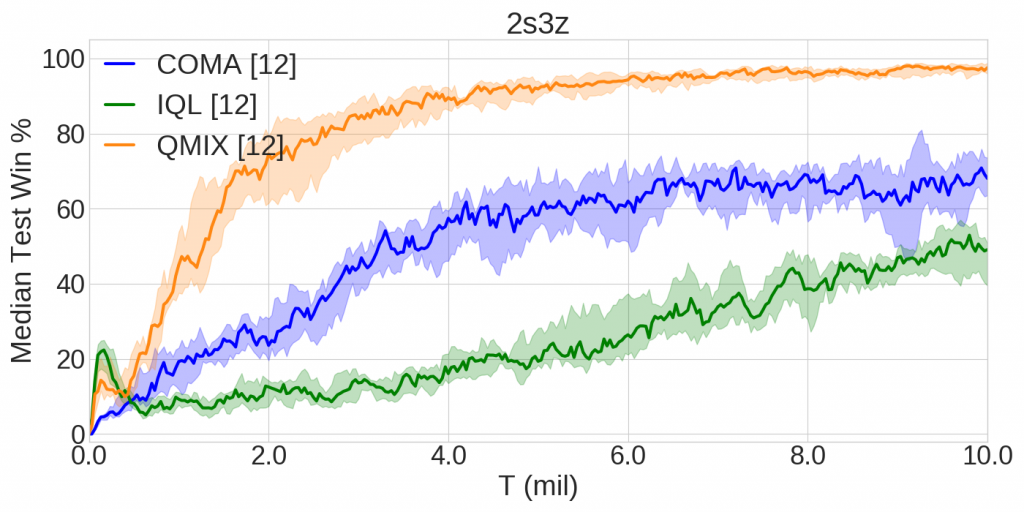

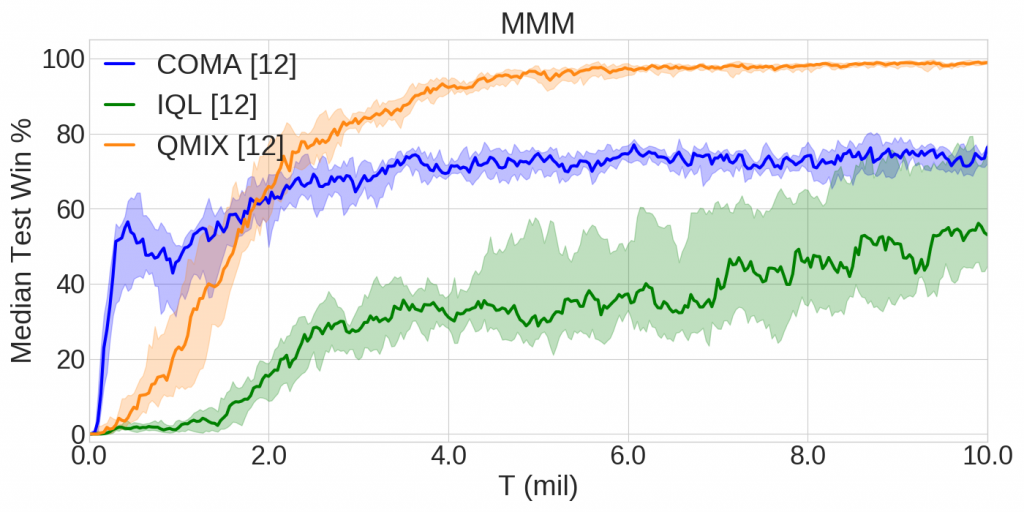

The following graphs illustrate the learning curves of QMIX, COMA, and Independent Q-Learning state-of-the-art methods on two SMAC scenarios, namely MMM and 2s3z. They present the median win rate of the methods across 12 random runs during the training that lasted 10 million environment steps (25%-75% percentile is shaded).

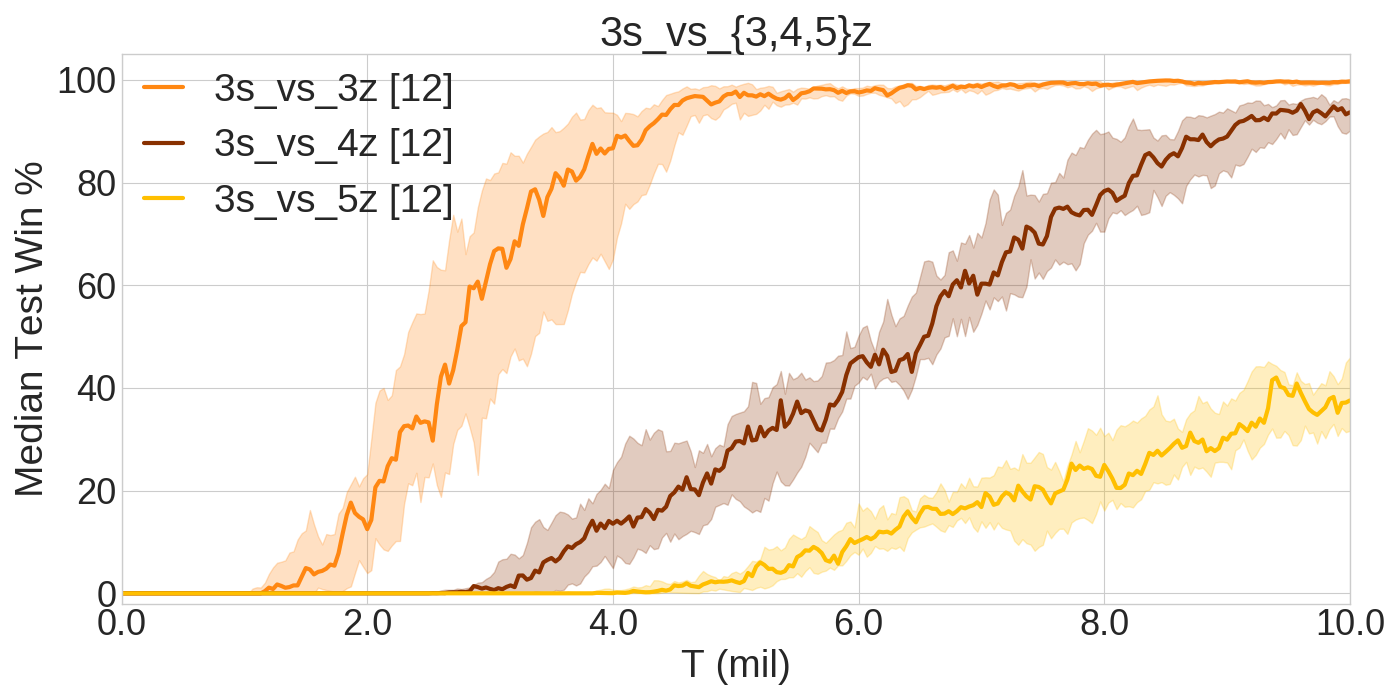

The scenarios in SMAC have incremental difficulty. For example, 3s_vs_3z, 3s_vs_4z, and 3s_vs_5z scenarios challenge 3 allied Stalkers to combat against 3, 4 and 5 enemy Zealots respectively. Stalkers are very vulnerable to Zealot attacks. Hence, they need to kite in order to stand a chance. As the following graph highlights, kiting becomes increasingly harder with the increase of enemy Zealots, requiring a more fine-grained control and additional training time.

Further results of our initial experiments using the SMAC benchmark can be found in the accompanying paper.

PyMARL

To make it easier to develop algorithms for SMAC, we are also open-sourcing our software engineering framework PyMARL. PyMARL has been designed explicitly with deep MARL in mind and allows for out-of-the-box experimentation and development.

Written in PyTorch, PyMARL features implementations of several state-of-the-art methods, such as QMIX, COMA, and Independent Q-Learning.

In collaboration with the BAIR, some of the above algorithms have also been successfully ported to the scalable RLlib framework.

We heavily appreciate contributions by the community – please feel free to fork the PyMARL github repository!

Conclusion

In this post, we presented SMAC – a set of benchmark challenges for cooperative MARL. Based on the game StarCraft II, SMAC focuses on decentralised micromanagement tasks and features 22 diverse combat scenarios which challenge MARL methods to handle partial observability and high-dimensional inputs.

We are looking forward to accepting contributions from the community and hope that SMAC will become a standard benchmark environment for years to come.

Links

- Learn how to use SMAC from the Github repository

- Develop new algorithms with our PyMARL framework

- Cite the release paper if you use SMAC or PyMARL in your research

Blogpost: Mikayel Samvelyan, Gregory Farquhar, Christian Schroeder de Witt, Tabish Rashid, Nantas Nardelli, Jakob Foerster, Shimon Whiteson.

This blogpost was originally posted on the WhiRL blog.